This article deals with the question of possible reasons for Conrad Gessner quoting an aphorism from Julian the Apostate’s letter (Ep. 23, to Ecdicius, prefect of Egypt) under the name of Marcus Aurelius in the preface to his Bibliotheca universalis, the first European universal bibliography (1545). Basing on the articles in Bibliotheca devoted to the above-mentioned authors, we can conclude that Gessner was directly acquainted with Julian’s letters (he obviously relied on the collection of Greek letters published by Aldus Manutius in 1499 under the title Epistolae diversorum philosophorum, oratorum, rhetorum), whereas no texts of Marcus (including fragmentary ones) were available to him by 1545. The topic of the search for a library and the question of how to treat the books written by religious opponents, which occupy a central place in Julian’s letter to Ecdicius, must have attracted Gessner’s attention, especially since the solution proposed by Julian turned out to be consonant with Gessner’s thoughts expressed in Bibliotheca. Thus, the false attribution of the quotation, undoubtedly deliberate, was, on the one hand, to prevent possible reproaches from conservative readers for quoting an anti-Christian author, and, on the other hand, to draw attention of a competent reader to Julian’s text

Идентификаторы и классификаторы

- SCI

- Языкознание

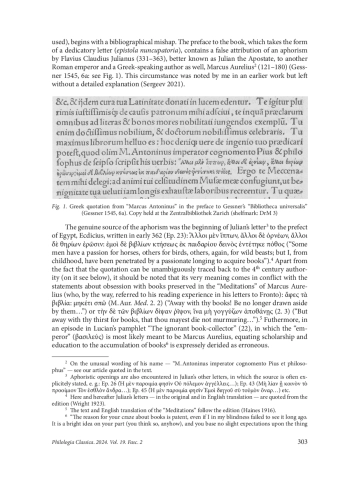

“Bibliotheca universalis” (1545) by Conrad Gessner, which laid the foundation for the European bibliography of printed books and universal bibliography in general,1 and is mainly characterized by the reliability of information (including references to the sources used), begins with a bibliographical mishap. The preface to the book, which takes the form of a dedicatory letter (epistola nuncupatoria), contains a false attribution of an aphorism by Flavius Claudius Julianus (331–363), better known as Julian the Apostate, to another Roman emperor and a Greek-speaking author as well, Marcus Aurelius 2 (121–180) (Gessner 1545, 6a: see Fig. 1). This circumstance was noted by me in an earlier work but left without a detailed explanation (Sergeev 2021)

Список литературы

1. Blair A. Too Much to Know: Managing Scholarly Information before the Modern Age. New Haven, London, Yale University Press, 2010.

2. Bowersock J. W. Julian the Apostate. Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1978.

3. Elm S. Sons of Hellenism, Fathers of the Church: Emperor Julian, Gregory of Nazianzus, and the Vision of Rome. Berkeley, University of California Press, 2012.

4. Epistolae diversorum philosophorum, oratorum, rhetorum sex et viginti. Venetiis, A. Manutius, 1499.

5. Gessner C. Bibliotheca universalis. Tiguri, Ch. Froschauer, 1545.

6. Gessner C. (ed.). M. Antonini Imperatoris Romani et Philosophi De seipso seu vita sua Libri xii. Graece et Latine. Tiguri, A. Gessner, 1559.

7. Haines C. R. (ed., transl.) The Communings with himself of Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Emperor of Rome, together with his speeches and sayings. London, W. Heinemann, 1916.

8. Harmon A. M. (ed., transl.). Lucian: in eight volumes. Vol. III. London, W. Heinemann, 1921.

9. Leu U. B. Conrad Gesner als Theologe: Ein Beitrag zur Zürcher Geistesgeschichte des 16. Jahrhunderts. Berlin, Peter Lang, 1990.

10. Nulle S. H. Julian and the Men of Letters. The Classical Journal 1959, 54 (6), 257-266.

11. Pinon L. Conrad Gessner and the historical depth of Renaissance natural history. In: Pomata G., Siraisi N. (eds). Historia: Empiricism and erudition in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge, M. I. T. Press, 2005, 241-268.

12. Sabba F. La “Bibliotheca universalis” di Conrad Gesner: Monumento della cultura europea. Roma, Bulzoni editore, 2012.

13. Sergeev M. Bibliographical Scrupulousness and Philological Zeal: Conrad Gessner Working on the editio princeps of ‘Ad se ipsum’. Erudition and the Republic of Letters 2021, 6, 349-375. EDN: KUGNEN

14. Sicherl M. Griechische Erstausgaben des Aldus Manutius: Druckvorlagen, Stellenwert, kultureller Hintergrund. Paderborn, F. Schöningh, 1997.

15. Simmler J. Epitome Bibliothecae Conradi Gesneri. Tiguri, Ch. Froschauer, 1555.

16. Wright W. C. (ed., transl.). The works of the emperor Julian. Vol. III. London, W. Heinemann, 1923.

17. Zedelmaier H. Bibliotheca universalis und bibliotheca selecta: das Problem der Ordnung des gelehrten Wissens in der frühen Neuzeit. Köln, Böhlau, 1992.

Выпуск

Другие статьи выпуска

In Antiphon’s speech “Prosecution of the Stepmother for Poisoning”, one of emphasized motives is the opposition between, on the one hand, the author of the criminal plan and organizer of the murder, and on the other hand, the immediate executor. The accuser claims that his stepmother plotted to kill her husband and deceived a female slave into adding poison to his wine. The slave was executed as the murderer, but the accuser seeks to prove that the true guilt lies with the stepmother, as she conceived the crime. The manuscript text (20) reads a participle χειρουργήσασα, ‘the one who enacted’, attributed to the stepmother. Friedrich Blass, in his 1871 edition, transposed the words καὶ χειρουργήσασα, referring them to the slave who poured the poison into the wine, believing, as she was told by the accused, that it was a love potion. By doing this, Blass emphasized the distinction between the plan and its execution. Almost all editors accepted this rearrangement. At the same time, some scholars prefer the manuscript reading. Reiske, supported by Maetzner, suggested a literal understanding of the participle, ‘the one who prepared the poison’. Wilamowitz considered χειρουργήσασα a rhetorical exaggeration. Adelmo Barigazzi and Ernst Heitsch understood the participle attributed to the stepmother in the manuscripts as a way to shift the entire responsibility for the murder — both the criminal idea and its execution — onto the stepmother. Here I present arguments in favor of the manuscript reading and variants of interpreting its meaning

This article is devoted to the history of stylometry and its development at an early stage. Stylometry is an applied philological discipline that considers style as a set of quantitative parameters. Stylometry arose on the material of classical studies. Using the example of the most reliable and authoritative stylometric method to date — Burrows’ Delta — the advantages and disadvantages of this type of analysis are examined. The genesis of the term “stylometry” is established. In the seminal book of G. Martynenko “Fundamentals of Stylometry” it is indicated that it was coined by the German classical philologist W. Dittenberger. The study reveals that the term “stylometry” actually existed in the 19th century in the meaning of ‘the art of measuring columns’, and it is not used in Dittenberger’s works. This term was introduced by W. Lutoslawski, who tried to solve the problem of periodisation of Plato’s dialogues. It turns out that “stylometry” was first used in a new meaning on May 21, 1897, during a report by W. Lutoslawski at the Oxford Philological Society. In Russia, the term first appears in a review in 1898 in the form стилометрия, and in Morozov’s 1915 article in the form стилеметрия, which became widespread in the Soviet academic community

В статье рассматривается малоизученный в науке вопрос о воспроизводстве кадров по классической филологии в Петроградском/Ленинградском университете в конце 1910-х — 1920-е гг. Материалами служат в основном архивные делопроизводственные документы и изданные в исследуемый хронологический отрезок «Обозрения преподавания» Ленинградского университета. Изучение эволюции отдельного направления подготовки позволило отказаться от наметившейся в постсоветской историографии тенденции создания образа дореволюционного поколения ученых только как жертвы политики большевиков и продемонстрировать стратегии приспособления профессоров «старой» школы к новой действительности, в которой наука о классической древности потеряла государственную поддержку. Выявляется стремление старшего поколения адаптировать свои представления о системе подготовки кадров по классическим дисциплинам и педагогический опыт к изменяющимся условиям. Даже сложившаяся веками система изучения на университетских занятиях древних авторов при необходимости позиционировалась как «инновационный» бригадно-лабораторный метод обучения, который навязывался Наркомпросом. До 1927 г. за многочисленными отделениями, циклами, уклонами удавалось сохранять в общих чертах прежний подход к подготовке филолога-классика, который зиждился на комплексном характере антиковедческой дисциплины. В статье выявлен ряд тенденций в высшей школе 1920-х гг., повлиявших на состояние образования по классической филологии. Введение так называемых «общественных дисциплин», удельный вес которых в программах обучения постоянно рос, привел к сокращению дисциплин профессиональных. В последнюю треть 1920-х гг. под лозунгами борьбы с «многопредметностью» происходило сворачивание узких специализаций. В 1928 г., с началом «культурной революции», возобладала ориентация на подготовку кадров с практическими навыками

Выход в свет первого тома сочинений А. С. Пушкина в 1899 г. побудил филолога-классика Виктора Карловича Ернштедта перечитать его лицейскую лирику, насквозь пронизанную античными мотивами. В философической оде Пушкина «Усы», написанной в 1816 г., он обратил внимание на строчку «где драмы тощие Клеона?» и посвятил ей небольшую заметку, которая впервые публикуется и комментируется. В ней В. К. Ернштедт высказал остроумную догадку о том, что Пушкин имел в виду малоизвестного древнего драматурга Клеофонта, но по ошибке написал имя известного политика Клеона. В. К. Ернштедт задается вопросом, из какого источника поэт мог знать о Клеофонте. Сведения о «Поэтике» Аристотеля, где встречается имя Клеофонта, лицеисты могли почерпнуть из первого тома труда Ж. Ф. Лагарпа «Лицей, или Курс древней и новой литературы» — настольной книги в преподавании литературы в Царскосельском Лицее. Однако имя Клеофонта здесь не встречается, нет его и в дидактическом сочинении Н. Буало-Депрео «Поэтическое искусство», доступном лицеистам на языке оригинала и в русском переводе. Филолог-классик переоценил культурный багаж поэта-лицеиста, обширность и глубину лицейского образования. Много позже пушкинисты установили, что под именем Клеона скрывался современник А. С. Пушкина — посредственный поэт А. А. Шаховской. В. К. Ернштедт подошел к тексту Пушкина с позиций филологаклассика, недооценив культурный контекст эпохи. Но его ошибка сама по себе весьма примечательна, а поставленные им вопросы говорят о его намерении продолжить исследование и показывают направление будущих поисков

В статье представлен текстологический и компаративный комментарий к встречающимся в романе Д. С. Мережковского «Смерть богов. Юлиан Отступник» цитатам из эпических поэм Гомера: к Il. 5, 83 (дана на греческом языке с русским переводом) и к Od. 14, 57–58 (только в русском переводе). Анализ черновиков русского писателя позволяет установить, что эти стихи и их переводы были заимствованы через текстыпосредники. Результаты сопоставления содержащих гомеровские строки мест (в романе, исторических источниках, а также в произведениях Й. фон Эйхендорфа, Г. Ибсена, Ф. Дана, Г. Видала, привлеченных в качестве дополнительного материла для сравнения) и анализа их роли в архитектонике первой части трилогии «Христос и Антихрист» демонстрируют, как Мережковский, изменяя форму и значение употребленных цитат, включает их в художественную структуру своего произведения. Гекзаметр Il. 5, 83 обретает смысл мистической словесной формулы и становится центральным элементом фрактальной по своему типу (многократно воспроизводящей три фазы инициации) сюжетной системы, которая передает становление Юлиана как императора-отступника. Стилистический акцент этого стиха может быть определен как один из источников образности произведения Мережковского: русские варианты, соответствующие греческому πορφύρεος, и семантически связанные с ними лексемы употреблены здесь подобно тому, как это прилагательное использовано в «Илиаде», и проявляются в ключевых эпизодах. Стихи Od. 14, 57–58, концентрирующие общие для греко-римского язычества и христианства ценностные темы, также обретают дополнительное значение, поддерживая разрабатываемую с первых глав линию сопоставления Юлиана со стремящимся на родину Одиссеем

В статье рассматривается вопрос заимствований в латинском тексте «Слова похвального Елисавете Петровне» М. В. Ломоносова. Так как М. В. Ломоносов получил прекрасное образование в Славяно-греко-латинской академии, где познакомился с трудами великих античных авторов, он мог осознанно или неосознанно подражать им при написании текстов на латинском языке. Что касается «Слова», источниками некоторых идей для М. В. Ломоносова уже были признаны Цицерон и Плиний Младший, в данной статье этот тезис также дополняется некоторыми лексическими параллелями. На этом фоне особенно интересны заимствования из «Героид» Овидия, представляющих собой поэтические послания влюбленных героинь мифов, а не ораторское произведение. В качестве источников латинского варианта «Слова» М. В. Ломоносова можно выделить два эпизода (Ov. Her. 6, 11; 7, 69–70), которые иллюстрируют известные и запоминающиеся мифологические образы: Ясона, сеющего зубы дракона в целях получения золотого руна, и Дидоны, совершающей самоубийство из-за разлуки с Энеем. При этом Овидий в Her. 6, 11 использует глагол adolesco, а М. В. Ломоносов переводит русский текст «Слова», используя глагол adoleo. Хотя в случае «Слова» жанровая природа «Героид» делает эту работу менее подходящей для подражания, чем речи Цицерона и «Панегирик императору Траяну» Плиния, заимствованные образы выглядят уместно в тексте М. В. Ломоносова, тем более что они являются результатом длительного интереса М. В. Ломоносова к этому произведению: М. В. Ломоносов приобрел издание Овидия еще при обучении в Марбурге, а некоторые фрагменты «Героид» переводил для «Краткого руководства к риторике», опубликованного за год до написания «Слова»

This piece studies the Portuguese version of the so-called Notarial Latin, the Latin of medieval documents. The author briefly overviews the reasons why these written records have been scarcely explored — the low availability of texts, the unreliability of existing editions and the perception of Notarial Latin as a corrupted language. The chronological framework of Notarial Latin, its correlation with Late and Medieval Latin and its sociolinguistic peculiarities are described. It is suggested to primarily focus on the morphosyntax of Notarial Latin. The results of the analysis of eighteen texts created between 1033 and 1183 are then presented followed by the analysis of various deviations from the grammatical norm of Latin caused by the interference of Galician-Portuguese. In nominals, there is a violation of the norms for the use of some prepositions (foremost, the preposition de). The case system generally remains. In the verb system, the regular use of Latin Futurum II in the function of the Portuguese Futuro de Conjuntivo which developed on its basis is evident. However, contrary to expectations, there are practically no traces of Romance verb analyticity. On the syntactic level, there is a tendency towards the SVO word order. The frequent cases of Romance interference indicate supposedly the most profound transformations that took place during the formation of Galician-Portuguese from vernacular Latin. It is concluded that the study of Notarial Latin is promising for a contrastive typology of Latin and Romance languages

In Roman literature the negative image of a stepmother exists at least from the Late Republican times onwards. The Roman authors underline the cruelty of stepmothers and their mistreatment of stepchildren. Sometimes the amorous stepmother wants to seduce her adult stepson and, after the latter repudiates her love, begins to victimize him. In Latin declamations the noverca is often presented as a venefica who, motivated mainly by quarrels over inheritance, aims to poison her stepson (or sometimes husband; in this case she tries then to shift the blame onto the stepson). Cicero, when in 66 B. C. he defended in the court a Roman knight A. Cluentius Habitus, exploits these negative stereotypes extensively. One of the main characters in his speech Pro Cluentio is the mother of his client, Sassia, who, according to Cicero, is the true soul of the accusation against Cluentius. Cicero presents Sassia not as a mother, but as a saeva noverca who hates her own son and wants to destroy him. The skilful use of these (and some other) stereotypes, which were undoubtedly shared by a large part of Cicero’s audience, as well as corresponding literary topoi probably contributed significantly to the success of Cicero’s defence.

This paper considers one of the key events in the course of the post-Gracchan agrarian reform when the lex Thoria agraria was passed. This law sought to counter the effects of the political crisis brought about by the agrarian reform of Tiberius Gracchus. The author puts forward a hypothesis that the so-called sententia Minuciorum, an epigraphic document which is dated to 117 BC, can be regarded as a source for the agrarian law of Spurius Thorius. The argument is based on both ancient narrative of the lex Thoria agraria (Cicero, Appian) and two well-known inscriptions from the post-Gracchan time, the Sententia Minuciorum and the agrarian law of 111 BC. The author points out that the Sententia Minuciorum is the first epigraphic document in which a rent imposed on any part of the ager occupatorius is mentioned and that a rent paid in silver is also attested in the post-Gracchan time (117 BC) for the very first time. This fact could be well combined with Appian’s narrative of three post-Gracchan agrarian laws and the lex Thoria agraria, in particular (App. BC 1. 27). In conclusion, the author points out that the enactment of the lex Thoria agraria must be regarded as an historical triumph of the large landowners in Rome, because its provisions, as discussed above, denied poor Romans (by means of land distribution) direct access to the resources of the ager publicus populi Romani

A comparative analysis of the chapter titles and text of the first book of the late antique military treatise Strategikon allows to put forward the hypothesis that its text was constituted in several stages. Of particular importance here are the wording of the titles and the peculiar beginnings or introductions to most of the chapters, which summarise the content of the preceding sections. A comparison of the passages clearly shows the sequence of formation within each chapter. We should assume at least 5 consecutive phases of text development: author and 4 editors. At first (phase 1a–1b), on the basis of the extant sources, the author of the book created as part of the treatise a text in four sections, organised by the beginnings according to the scheme of genetivus absolutus (primary chapters *1, *2 + 3, *4, *5 + 9). Then another editor (Leg, phase 2) inserted into this codex in the middle of the text *5 + 9 two bifolia with the text of military laws organised by μετὰ-constructions (*6 + 7, *8), resulting in the actual division of the text *5 + 9 into two sections *5 and 9. The next editor (phases 3a–3b) then rewrote the entire text into a new codex, providing it with headings (following the πῶς… scheme), what consolidated the division of the text into seven chapters (1, 2 + 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 + 8, 9), but he could not, however, fully understand the system of incipits of the original text. The new editor (Optim) made a series of additions in the form of glosses and inserted leaves (phase 4). The main development of the text was completed in the next phase (5a–5b–5c), when two new headings (3 and 8), structured in a different scheme (περὶ…), an introduction to chapter 8, and a general table of contents for Book 1 were inserted into this codex. The text was then rewritten into a new, third codex, which fixed the position of interpolations in the text.

This paper is dedicated to the analysis of the intertextual relationship between Sophocles’ Antigone and the plays of Aeschylus, especially the Theban trilogy. It is shown that Sophocles in this play creates the situation that is radically different from that of Aeschylus’ tragedies. The main differences are the attitude towards “peace in death” and towards the ancestral curse. In Sophoclean play, by contrast with Aeschylus, death is not the end of the strife — at least not until those in power acknowledge that it is; blood ties are not enough for belonging to the cursed family, and this belonging is not necessarily envisaged in negative terms. To illustrate the utter inadequacy of the Aeschylean approach to the world and the events of his tragedy, Sophocles embodies such approach in his Chorus and provokes, during the course of the play, the growing disappointment of the spectator by it. The Chorus is irresponsive when directly addressed, annoyingly counterproductive during the commos with Antigone and prone to change their opinion and perspective too quickly and radically. At the fifth stasimon Sophocles, by the reference to another Aeschylus’ tragedy, this time the Eleusinians, gives the spectator the short-living hope for the rescue of Antigone. This trap is also intended to disappoint the spectators and show them the inadequacy of the Chorus’ Aeschylean perspective

Издательство

- Издательство

- СПБГУ

- Регион

- Россия, Санкт-Петербург

- Почтовый адрес

- Россия, 199034, Санкт-Петербург, Университетская наб., д. 7–9

- Юр. адрес

- 199034, г Санкт-Петербург, Василеостровский р-н, Университетская наб, д 7/9

- ФИО

- Кропачев Николай Михайлович (РЕКТОР)

- E-mail адрес

- spbu@spbu.ru

- Контактный телефон

- +7 (812) 3282000

- Сайт

- https://spbu.ru/