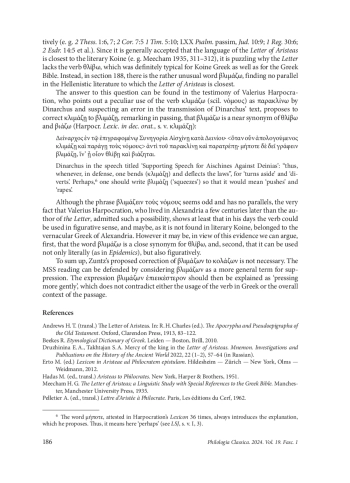

This piece explores the difficult expression βλιμάζων ἐπιεικέστερον found in the MSS of the Letter of Aristeas, in the section describing how Ptolemy II Philadelphus puts questions to the interpreters he has invited in Alexandria and receives advice to treat his subordinates with kindness and not to impose harsh punishments on them (Ep. Arist. 188). According to the most scholars, who have published the Letter of Aristeas, including P. Wendland, H. Thackeray, H. Andrews, R. Tramontano, and R. Shutt, the verb βλιμάζω in the answer of the Jewish sage means ‘to chastise’. However, this interpretation is not supported by the actual usage of the verb in ancient Greek. In fact, this word, which is often used in comedy, usually means ‘to grope’ and seems quite out of place coming from the sage. Günther Zuntz pointed out that the verb βλιμάζω is not appropriate and suggested correcting βλιμάζων to κολάζων, which is accepted by A. Pelletier (1962) and is supported in the recent studies on the Letter (Wright [2015] and Erto [2012]). The consideration of the correction and the analysis of the wordusage in ancient Greek literature, as well as the examination of the explanations provided by lexicographers, where the verb θλίβω and its derivatives are used as synonyms for βλιμάζω, lead us to the conclusion that Zuntz’s suggestion is not necessary und should be rejected. The reading βλιμάζων, confirmed by the manuscripts, may be retained by supposing that it implies pressure in a broader sense

Идентификаторы и классификаторы

- SCI

- Языкознание

In the large part of the Letter of Aristeas the 72 Jewish sages, invited by the king Ptolemy II for translating the Hebrew Pentateuch into Greek, take part in so called Symposia, where they give answers to the different questions of the king. According to the author of the Letter, the king paid high tribute to their replies; moreover, in the section 294 he gratefully acknowledges that he has benefitted from their teaching about the kingship. In the section 188 one of the sages, replying to the question about conserving the kingdom unimpaired, gives him advice to be clement with his subordinates and furthermore to punish them more leniently than they deserve (in case they would turn out guilty) in order to lead them to a change of mind. The similar idea is represented also in the sections 191–192 and 207–208, where the king receives the precept to use clemency imitating the manner of God

Список литературы

1. Andrews H. T. (transl.) The Letter of Aristeas. In: R. H. Charles (ed.). The Apocrypha and Pseudoepigrapha of the Old Testament. Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1913, 83-122.

2. Beekes R. Etymological Dictionary of Greek. Leiden - Boston, Brill, 2010.

3. Druzhinina E. A., Takhtajan S. A. Mercy of the king in the Letter of Aristeas. Mnemon. Investigations and Publications on the History of the Ancient World 2022, 22 (1-2), 57-64 (in Russian).

4. Erto M. (ed.) Lexicon in Aristeae ad Philocratem epistulam. Hildesheim - Zürich - New York, Olms - Weidmann, 2012.

5. Hadas M. (ed., transl.) Aristeas to Philocrates. New York, Harper & Brothers, 1951.

6. Meecham H. G. The Letter of Aristeas; a Linguistic Study with Special References to the Greek Bible. Manchester, Manchester University Press, 1935.

7. Pelletier A. (ed., transl.) Lettre d’Aristée à Philocrate. Paris, Les éditions du Cerf, 1962.

8. Schmidt M. Der Brief des Aristeas an Philokrates. In: A. Merx (Hg.). Archiv für wissenschaftliche Erforschung des Alten Testamentes. 1. Bd. Halle, Verlag des Buchhandlung des Weisenhauses, 1869, 242-312.

9. Shutt R. (transl.) The Letter of Aristeas. In: J. H. Charlesworth (ed.). The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha. Vol. 2. New York, Doubleday, 1985, 7-34.

10. Smith Wesley D. (ed., transl.) Hippocrates. Vol. 7. Cambridge Massachussets - London, Harvard University Press, 1994.

11. Thackeray H. St. J. (transll.) The Letter of Aristeas. London, Macmillan, 1904.

12. Tramontano R. (ed., transl.) La Lettera di Aristea a Filocrate: Introduzione, testo versione e commento. Naples, Ufficio succursale della civiltà cattolica in Napoli, 1931.

13. Wendland P. (ed.) Aristeae ad Philocratem epistula cum ceteris de origine versionis LXX interpretum testimoniis. Leipzig, B. G. Teubner, 1900.

14. Wendland P. (transl.) Aristeasbrief. In: E. Kautsch (Hg.). Die Apokryphen und Pseudepigraphen des Alten Testaments. Bd. 2. Tübingen, Mohr Siebeck, 1900, 1-31.

15. White M. L., Keddie A. G. (ed., transl.) Jewish Fictional Letters from Hellenistic Egypt. The Epistle of Aristeas and Related Literature. Atlanta, SBL Press, 2018.

16. Wright III B. G. The Letter of Aristeas. ‘Aristeas to Philocrates’ or ‘On the Translation of the Law of the Jews’. Berlin - Boston, Walter de Gruyter, 2015.

17. Zuntz G. Zum Aristeas Text. Philologus 1958, 102, 240-246.

Выпуск

Другие статьи выпуска

This piece explores the difficult expression βλιμάζων ἐπιεικέστερον found in the MSS of the Letter of Aristeas, in the section describing how Ptolemy II Philadelphus puts questions to the interpreters he has invited in Alexandria and receives advice to treat his subordinates with kindness and not to impose harsh punishments on them (Ep. Arist. 188). According to the most scholars, who have published the Letter of Aristeas, including P. Wendland, H. Thackeray, H. Andrews, R. Tramontano, and R. Shutt, the verb βλιμάζω in the answer of the Jewish sage means ‘to chastise’. However, this interpretation is not supported by the actual usage of the verb in ancient Greek. In fact, this word, which is often used in comedy, usually means ‘to grope’ and seems quite out of place coming from the sage. Günther Zuntz pointed out that the verb βλιμάζω is not appropriate and suggested correcting βλιμάζων to κολάζων, which is accepted by A. Pelletier (1962) and is supported in the recent studies on the Letter (Wright [2015] and Erto [2012]). The consideration of the correction and the analysis of the wordusage in ancient Greek literature, as well as the examination of the explanations provided by lexicographers, where the verb θλίβω and its derivatives are used as synonyms for βλιμάζω, lead us to the conclusion that Zuntz’s suggestion is not necessary und should be rejected. The reading βλιμάζων, confirmed by the manuscripts, may be retained by supposing that it implies pressure in a broader sense

В 1948–1954 гг. в ряде школ Советского Союза в учебную программу старшеклассников оказался включен латинский язык. Для проведения реформы С. П. Кондратьев и А. И. Васнецов написали учебник, переживший четыре издания, хрестоматию с отрывками из латинских произведений и методические рекомендации. Пособия составлялись в спешке без должного обсуждения их содержания. Новаторство, заключающееся в перегруппировке грамматического материала, ином подборе оригинальных латинских текстов (со включением отрывков из трудов Геродота, Юстина, Матвея Меховского, описывающих древнее состояние территорий, входивших в СССР), увеличении удельного веса историко-лингвистического материала в объяснении правил грамматики, встретило негодование со стороны профессионального сообщества филологов-классиков, которое с критикой обрушилось на учебно-методическое обеспечение курса. Кондратьев и Васнецов пошли на уступки лишь к 1953 г., но вместе с этим попы - тались усилить идейно-воспитательную компоненту в преподавании латинского языка. Подобранные для школьников адаптированные тексты и пословицы демонстрировали те черты характера римлян, которые соответствовали идеалу советского человека (коллективизм, смелость, твердость в преодолении трудностей, скромность, товарищество, бескорыстность и проч.). Ряд историко-лингвистических справок в учебниках имел аллюзии на современные события, а соответственно, играл роль политического воспитания (сохранение римлянами своего словарного фонда в условиях зависимости от этрусков ставится в параллель сопротивлению славянского населения Болгарии). Впрочем, вскоре, в 1954 г., эксперимент был свернут. В настоящей статье учебно-методический комплекс по преподаванию латинского языка рассматривается как маркер идеологических процессов. Автор приходит к выводу, что введение этого нового предмета в средние школы вписывается в общий вектор позднесталинского классицизма

The Portrait of a Young Man, or Self-Portrait, by Michael Sweerts, remains poorly studied, although this is one of the two known works, dated by the master himself, and dated 1656, a pivotal year in his biography. Beside the date the sheet pinned to the green tablecloth displays the signature and the moralizing motto: Ratio Quique [sic!] Reddenda. Titled as “The Bankrupt” the painting appeared in the collection of I. I. Shuvalov and with this apparently false title went first to the St Petersburg Academy of Arts, then to the Hermitage. The reading of it as belonging to the vanitas genre also leads away from the point. That the Young Man is not a frivolous embezzler, but a calculating businessman follows from parallels in Flemish and Dutch art. Neither is he a “melancholic”, however similar his posture may be to many of them. The key to Sweerts’ message is the Latin pinacogram, of which each word is capitalized and one is spelled in a somewhat extravagant manner (dat. quique). Rationem reddere evokes associations with the Gospel debt parables. Flemish painters had turned to this subject already in the early 16th century; Van Hemessen’s depiction of the Unforgiving Slave is likely to be one of Sweerts’ direct sources. The parallelism of earthly and heavenly “banking” is emphasized in Th. Halle’s engraving Redde rationem being part of Veridicus Christianus by J. David. The engraving and the portrait have a number of details in common, and the relative comment abounds in references to the debt parables. The Young Banker of the Hermitage portrait puts aside his counting and muses that the same debit-credit law operates in the other world, and that the list of debtors includes every one of us: to get that message across was so important to the fanatically catholic Sweerts that he styled the Latin inscription as the title of this list

Seven commentaries on D. 34.5.13.3 are examined, for the most part from the text found by the author in six codices written at the turn of the 13th century. The fugitive notice of Rogerius (d. around 1162) provoked attempts to correct the paragraph of the Digest and gave rise to a whole series of commentaries in the form of glosses, but also more developed commentaries, that of Ioannes Bassianus taking the form of a treatise. The Roman jurist has dealt in the paragraph with two variants of one and the same stipulation. Except for Bassianus, the medieval commentators could not understand the meaning of a fine distinction between these variants, and they were seduced by Rogerius’s idea that the elimination of the negative particle, employed in each of these variants, would have given an alternative character to two similar formulas of stipulation, by giving more movement and vigour to the thought of the Roman author. Rogerius wrote his entry in the first person. Next to this notice lies its paraphrase, written in the third person, probably by Placentin (d. between 1180 and 1192), Rogerius’ successor at the legal school of Provence. An interesting discussion focused on this paraphrase. The crux of the dispute was whether the negative particle should be eliminated in the first or second stipulation formula. In the heat of the discussion, the faithful followers of Bassianus, Hugolinus and Nicholas the Furious, largely ignored their master’s opinion.

This article opens a series devoted to investigating the sources of the ample zoological excursus (vv. 916–1223) in the Hexaemeron by George of Pisidia, a 7th-century Byzantine poet. Since the two attempts to find a general formula for George of Pisidia’s treatment of his models have led to directly opposite results (according to Max Wellmann, the poet distanced himself from pagan zoologists; according to Luigi Tartaglia, on the contrary, he drew material from them, favouring Aelian), it seems that the question of the poem’s sources should be addressed by a step-by-step examination of passages, paying attention to such evidence as the coincidence of minor details or words. In v. 1116 the unusual metaphor “aithyia, bending its winged cloud” (in the sense of “spreading its wings”) makes one think of an (unconscious?) association with Arat. Phaen. 918–920, where “a stretching cloud” is mentioned in the catalogue of storm’s signs in immediate juxtaposition to the flapping of the wings of seabirds. In vv. 1117–1124 (the self-cleansing of the ibis) the reference to Galen is not a mere metonymy (= “the most skillful physician”), as interpreters have hitherto thought, but points to the poet’s source: in the Galenic corpus this story is attested three times, and the passage closest to George of Pisidia’s account is [Galen.] Introd. 1.2. In vv. 1154–1159 (the structure of the web) the confused sequence of the stages of the spider’s work (first concentric circles, then radial threads), that contradicts both reality and (which is more important) the ancient tradition going back to Book IX of Historia animalium, seems to betray the influence of John Philoponus (De opif. mundi, p. 257, 24 sqq. Reinhardt). In Philoponus’ text this sequence is justified by the fact that his rhetorical passage describes, strictly speaking, not the web itself, but a drawing of it made by a “diligent geometer”.

The letter of recommendation was known in Antiquity as a separate genre of letter writing for which a certain set of compositional techniques and formulae were developed. In Byzantium, too, the letter of recommendation was in great demand: letters in which the author presents his protégé to the addressee and, as a rule, asks him to perform something for him are not difficult to find in the epistolary collections of many authors from the 4th to the 15 th century. Meanwhile, while the ancient letter of recommendation is well studied, the etiquette of this genre in the Byzantine tradition has hardly been investigated yet. The purpose of this piece is to characterize the etiquette norms of Greek letter of recommendation in the early Byzantine period (4th — early 7th centuries). The subject of the study are, first of all, literarische Privatbriefe, belonging to Libanius, Basil the Great, Gregory of Nazianzus, John Chrysostom, Synesius of Cyrene, Theodoret of Cyrrhus, Procopius of Gaza and others, but also private papyrus letters. Their analysis leads to the conclusion that there is a wide variability of the canons of the letter of recommendation, the absence of any rigid scheme that presupposes a clear sequence of structural elements. At the same time, it reveals six recurrent etiquette motifs, all of which are subordinated to a single goal — to persuade the addressee to patronize the recommended person. These motifs are analyzed in detail, and stable formulas are indicated for some of them. An attempt is made to determine to what extent the canons of Greek letters of recommendation of the 4 th–7th centuries go back to the ancient tradition. The letters of recommendation of Cicero and Pliny the Younger, as well as letters preserved on late antique papyri, are used as material for comparative analysis

Albrecht von Eyb (1420–1475) — was a canon, lawyer, and writer, one of the first northern humanists of the 15 th century. Eyb went down in the history of German literature primarily as the author of a treatise on marriage (Ehebüchlein, 1472) and as the first translator of Plautus’ comedies (part of Spiegel der Sitten, 1474). These significant works were preceded by the first humanist textbook of rhetoric written in Germany (Margarita poetica, 1459), which was the result of a 15-year stay in Italy and acquaintance with the humanist culture of the time. This article studies a cycle of Latin works (1451), Eyb’s first attempt at writing, which were later partially included in his Margarita. The four Latin opuscula, which I call here the ‘Bamberg Cycle’, were composed during Eyb’s one-year visit in Bamberg, when he was forced to interrupt his studies for a while to secure an income from his prebenda. The works of the cycle are united by the young author’s ambition to imitate humanist literature of his time, from which he borrows not only themes but also form. While it remains impossible to identify the precise audience for these works, or the reason that prompted Eyb to write them, a closer look at these works-exercises, which remain in the shadow of the author’s more successful works, allows us to trace the ways in which the ancient and humanist heritage was received and adapted. Thus, the works of the ‘cycle’ become important material not only for the study of Albrecht von Eyb’s writings, but also for the formation of humanist identity in mid-15 th-century Germany, at a time when the institutionalisation of the movement and its further flourishing were only just emerging

In this paper, the Latin language is analyzed in the context of typology of object incorporation. The authors draw on the research of Mithun, who considers incorporation on the basis of two obligatory conditions: first, the noun must be embedded in the verb, and second, the language must have parallel syntactic paraphrases with non-incorporated noun. The second criterion is so important that the phenomenon of incorporation is acknowledged to exist even in those languages where there is no complete integration of the noun into the verb, but only a certain syntactic compactness, provided there are parallel constructions. The latter type has been coined “noun stripping” and has launched the division of incorporation into two types, viz. “strong” and “weak” incorporation. Another important point of divergence between the incorporating languages is the change of the argument structure of the source verb, namely, the preservation or loss of transitivity of the incorporated complex. Taking all these parameters into account, the authors propose a new typology of object incorporation, including languages that have not previously been considered in the context of this phenomenon. This typology is not based on a strict opposition of incorporating and non-incorporating languages, but represents a kind of continuum in which the place of a language depends on whether it demonstrates: 1) full incorporation or only a close syntactic Noun–Verb compactness; 2) the presence of parallel syntactic paraphrases; 3) the detransitivisation of the resulting compound verb. The authors examine each criterion in detail as applied to Latin and show the place of Latin in this typology

This paper offers a comprehensive and critical review of the most significant studies on the possible alternation between two specific encodings that can express, in a generic sense, the Manner in which a verbal process is developed: adverbial expressions (ADV) and Secondary Predicates (SP). The main types of SP/ADV to be addressed here are those which are Subject and/or event oriented. Both general and typological works will be taken into account, as well as others more focused on the Latin language; the central criterion of the study will essentially be to distinguish and analyse approaches which are more or less favourable to seeing the two types of constituents as equivalent. A section devoted to the work of one of the Latinists who has contributed most specifically and notably to the issue under discussion (H. Pinkster) will also be included. Following a critical review of the criteria which have the greatest explanatory potential for explaining the issue, some analytical approaches will be proposed which are as objective as possible for a subsequent corpus study; these criteria include parameters pertaining to different linguistic levels: syntax, lexical-semantics, pragmatics, etc.: their application — here only tentatively discussed — will provide clear and measurable results on the problem and on those questions arising from the critical review itself.

The results of a comparative study of verb forms with aspectual semantics in Ancient Greek (Koine) (which has an overt category of aspect) and Latin (where aspect is rather a covert category), based on the Gospel of Mark, have shown that the expected correspondence of verb forms appears to be standard in the material as well: it is found in the majority of cases (97,6 % of the Ancient Greek Aorist translated by the Latin Perfect, and 89,4 % of the Ancient Greek Imperfect/ Present translated by the Latin Imperfect). Therefore, there must be a considerable semantic overlap between the Ancient Greek Aorist and the Latin Perfect forms and between the Ancient Greek Imperfect/Present forms and the Latin Imperfect forms. For each pair, there must be a common semantic core, corresponding in the first case to the perfective, and in the second case to the imperfective viewpoints. In the minority of cases, we find deviations from this standard correspondence. Some of them can be explained by the trivial fact that the context allows freedom in the choice of the aspectual viewpoint. However, in several cases, the discrepancies are not accidental and can be explained by the existence of specific differences between the grammatical systems of two languages. These include iterative contexts and contexts with speech verbs

The aim of this article is to analyse the theme of envy and its complexity in Josephus’ works in rhetorical and strategic sense rather than just as a literary topos. The paper focuses on two cases motivated by envy: Korah’s rebellion against Moses and the conflict between Josephus and John of Gischala. In these two cases, both the characteristics of envious persons and the richest descriptions of their sinister activities appear. The idea of Korah’s envy was not based on the Bible or the Second Temple literature or traditions but on Josephus’ own experiences from the period of his short-term command in Galilee (December 66 — July 67) when he was in conflict with envious John of Gischala. Thanks to this procedure, he was able to create the self-apologetic impression that his fate and that of Moses were intertwined because they had opponents with similar characteristics who were motivated by the same vice. Moreover, Josephus in both narratives follows the specific sequence according to which the envy leads to a “plot” (ἐπιβουλή), then to “false accusations” (διαβολή) and finally to a “sedition” (στάσις). He strategically used the theme of envy for his own apology to condemn his enemy, John of Gischala. The envy he felt disclosed the character of a person who was worse than Josephus in terms of personality traits. Josephus instead appears before the readers as a stoic sage who is free from weakness such as envy. At the same time the author draws attention to his own well-deserved success, thus the presence of envy becomes an indicator of his achievements. He conceals his own negative actions during his command in Galilee and tries to direct the audience’s attention to a specific arrangement of events that will lead to blaming his opponent. Keywords: Josephus, Korah, Moses, John of Gischala, conceptions of envy

A citharodic performance typically included a προοίμιον that preceded a νόμος. Theoretically, there are three possible options: a prooimion (1) was an inseparable introduction to a specific main part; (2) was not performed independently, but could precede various main parts; (3) was an independent piece. Most evidence points to option 2. Standard circumstances of performance must have stereotyped the subject matter that appeared in the introduction, so the proem became an autonomous song that could precede any narrative part, and even be performed independently (if there were no agonistic connotations and transitional formulas). Pseudo-Plutarch’s notions of ancient citharody (De mus. 1132В–С; 1132D; 1133B–C) are interpreted as follows: a proem addressed to the gods was a citharode’s own composition (hence ὡς βούλονται, despite its formal character and epic metre). It was immediately followed by a nome, whose epic narration could be either original or taken from Homer and other poets and set to music according to one of melodic patterns systemized by Terpander. Terpander’s proems likely offered two proofs of this theory: they ended with a formula of transition to another song, which itself did not follow. Apparently, the option to use someone else’s poetry in the main body led to the practice of writing down the proems without the subsequent nomes, so that they were seen as independent works. It is likely that Pseudo-Plutarch’s source was referring to minor Homeric hymns, since they correspond perfectly with the information that we have about citharodic proems

Издательство

- Издательство

- СПБГУ

- Регион

- Россия, Санкт-Петербург

- Почтовый адрес

- Россия, 199034, Санкт-Петербург, Университетская наб., д. 7–9

- Юр. адрес

- 199034, г Санкт-Петербург, Василеостровский р-н, Университетская наб, д 7/9

- ФИО

- Кропачев Николай Михайлович (РЕКТОР)

- E-mail адрес

- spbu@spbu.ru

- Контактный телефон

- +7 (812) 3282000

- Сайт

- https://spbu.ru/